Synergy of Mutually Supportive Teamwork

When it comes to advice on leadership, there is no shortage of books, articles, podcasts and lectures. Effective team leaders seem to be able to create and maintain a nurturing work environment for each team member and to provide an exiting vision for the entire team. In an insightful article, “Understanding Leadership,” published more than half a century ago, W. C. H. Prentice wrote that “[leader’s] unique achievement is a human and social one which stems from his [or her] understanding of his [or her] fellow workers and the relationship of their individual goals to the group goal…” (the original 1961 article was republished in the January 2004 issue of the Harvard Business Review, 82(1):102-9). Prentice also pointed out that “it is not hard to state in a few words what successful leaders do that makes them effective. But it is much harder to tease out the components that determine their success.” In this post, I would like to discuss one component of successful leadership, namely the leader’s role in fostering the culture and practice of mutual support among the team members.

Let me say from the outset that, in my opinion, no team leader can single-handedly create mutual support among team members: only the team members themselves can support each other. However, an effective leader will foster a mutually supportive team environment whereas an ineffective leader will neglect doing that. There are various signs by which we could recognize a mutually supportive team. It might not be possible to produce a complete list of such signs, but most of us would probably agree that team members who support each other

1. Forgive each other’s honest mistakes.

2. Show respect for and interest in each other’s areas of expertise.

3. Are willing to help other team members and to accept their help.

4. Rely on the support of the team leader.

5. Resolve conflicts by focusing on issues, not each other personalities.

6. Communicate openly, providing and accepting constructive feedback.

7. Are not afraid to appear as a “non-expert” during discussions.

8. Accept personal responsibility for team errors; and

9. Speak highly of each other to co-workers outside their team.

The more of these signs we observe, the surer we can be that the team members indeed support each other. The team members are not only the creators of a mutually supportive environment; each of them is also a beneficiary of it because, working in such an environment, he or she is able to contribute to a team effort more fully.

In this post I argue that the mutual support of team members has a kind of synergistic effect: as more and more team members fully contribute to the common effort, it becomes easier and easier for the other team members to do the same. As a consequence, a mutually supportive team is fully successful not only due to a “sum” of individual team member contributions, but also due to the synergy of their mutual support. My goal is to explore this synergistic effect using a Bayesian network model that encodes relations among the following key factors: the work contributions of team members, the probability that a mutually supportive environment exists, the extent to which the team leader fosters the mutual supportive environment, and the nine observable signs (listed above) by which we could recognize a mutually supportive team. In constructing the model, I made simple but plausible assumptions about the strength of the causal influences among the key factors. I will omit those technical details for brevity. The model was created using my favorite Bayesian network tool, GeNIe, a product of BayesFusion, LLC (https://www.bayesfusion.com/).

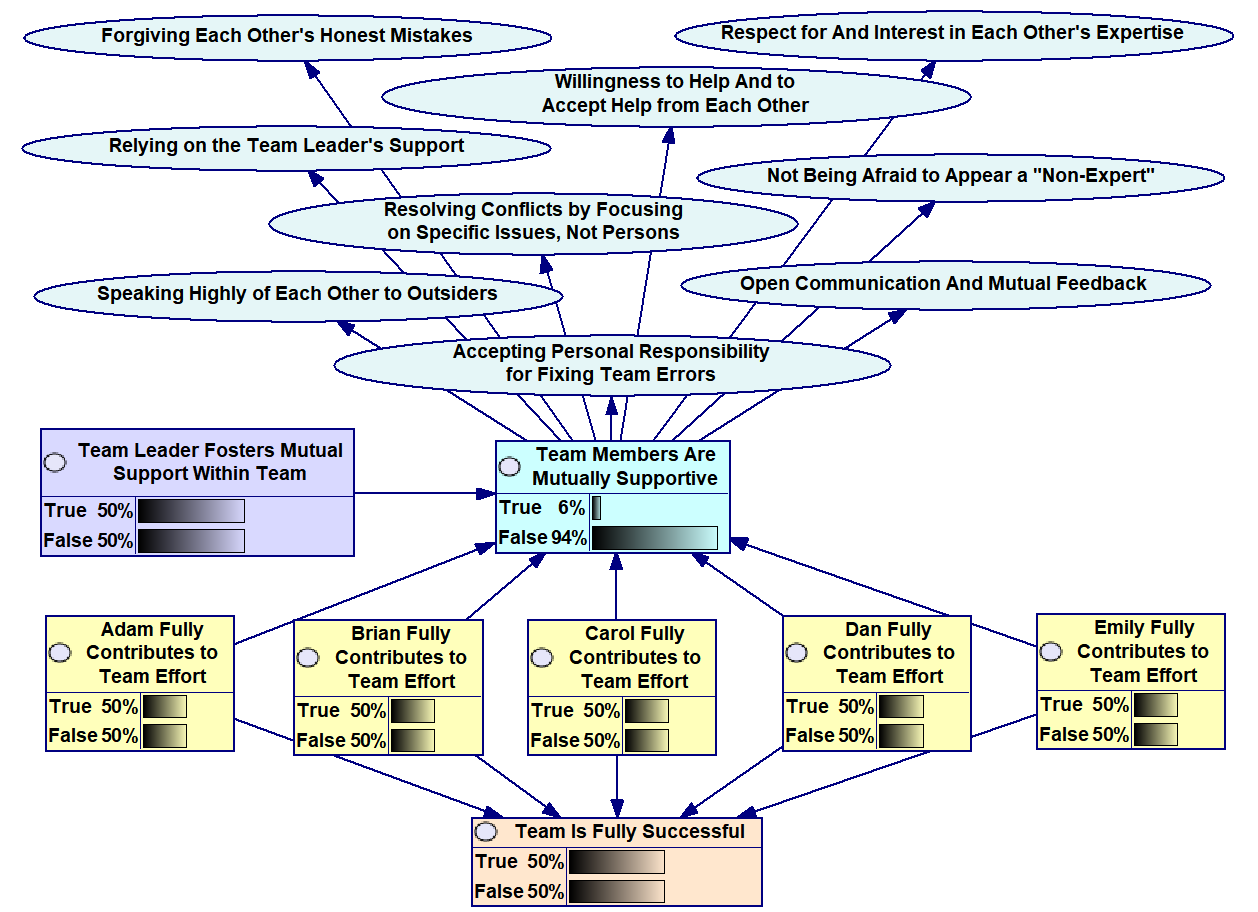

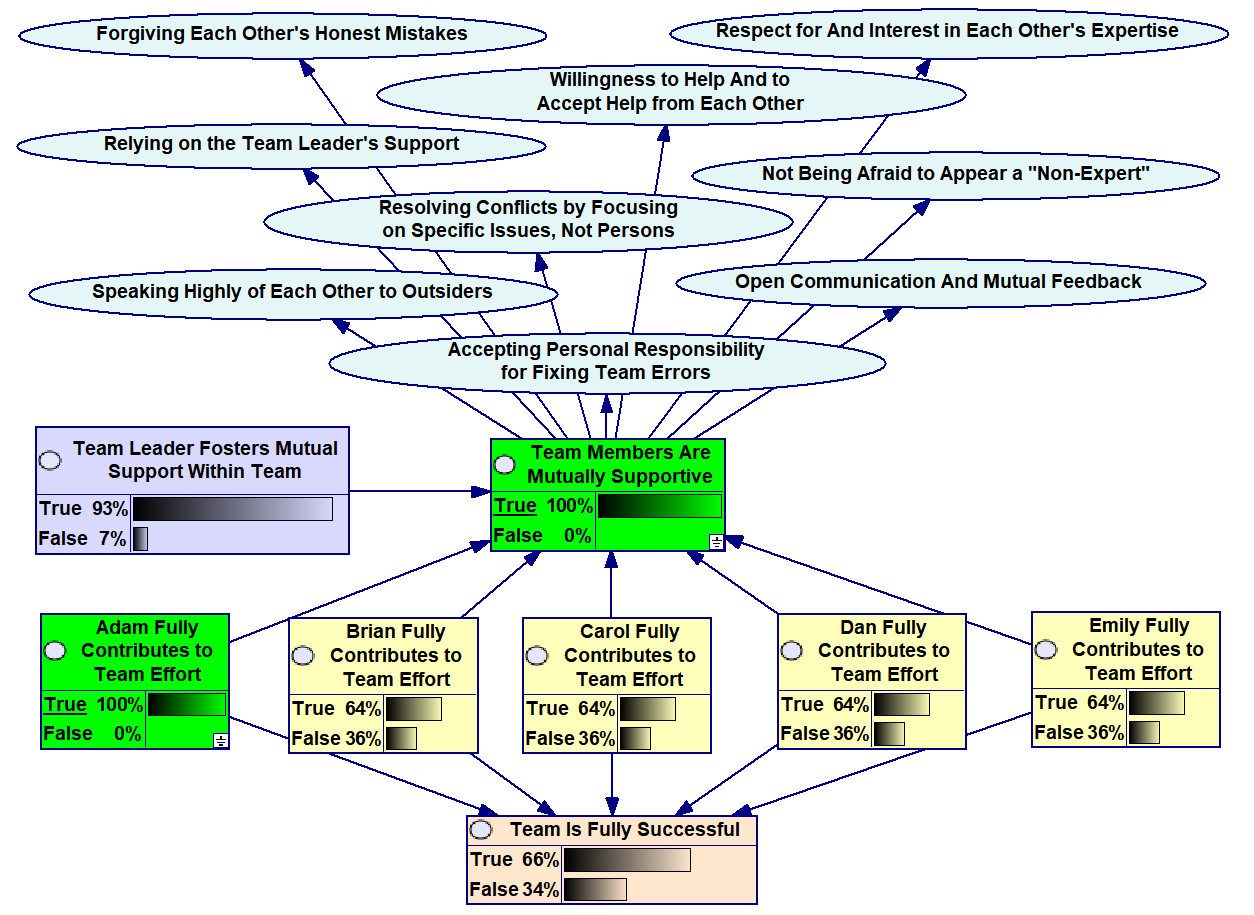

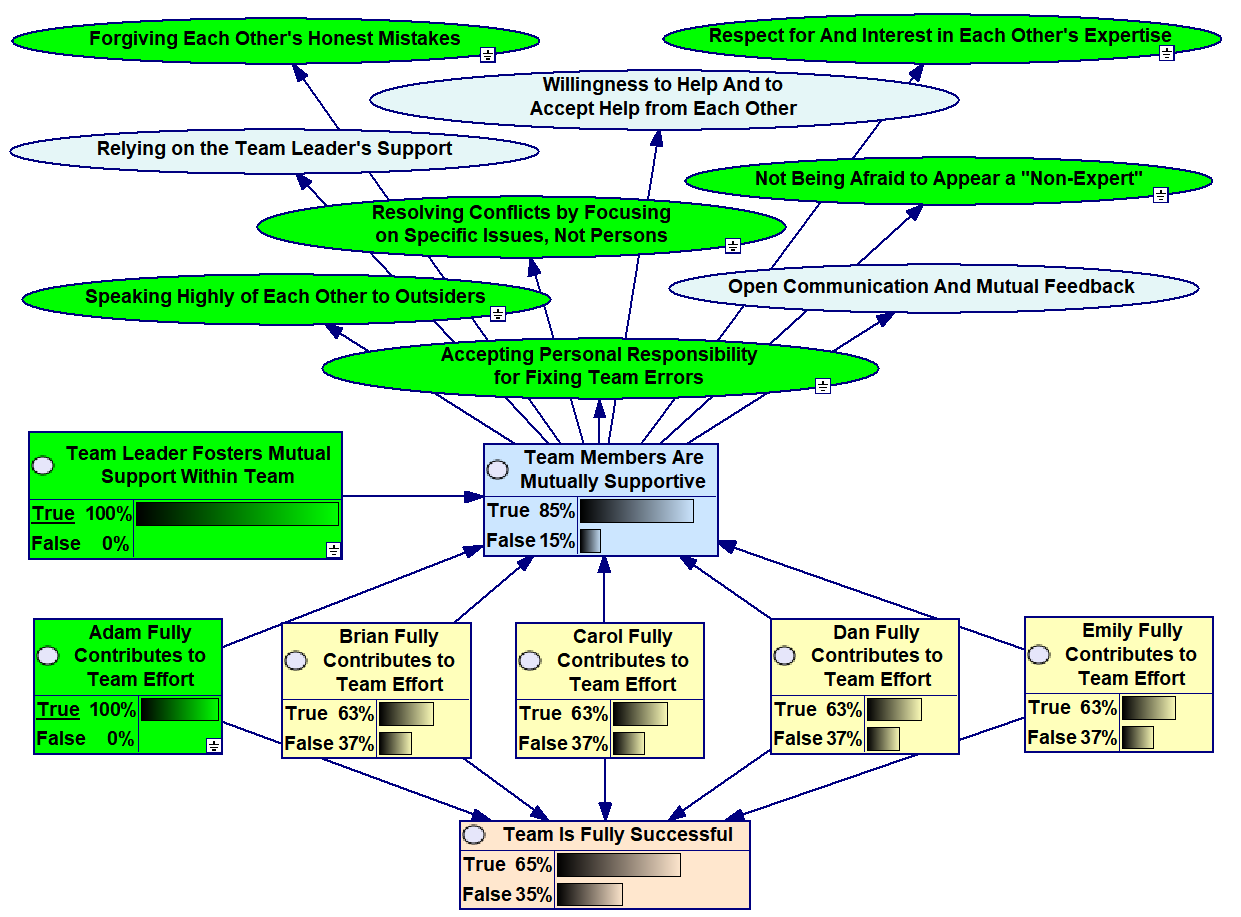

With these preliminaries out of the way, let us consider a team consisting of five people: Adam, Brian, Carol, Dan and Emily, denoted by the yellow nodes in the Bayesian network:

Figure 1

For the modeling purposes, all of them are considered to be “the same,” in the sense that each of them is 50% likely to fully contribute to the team effort. (This may appear as a disappointingly low probability, but—without any additional evidence—we consider this team to be average: not necessarily good and not necessarily bad.) By definition, the team is fully successful in this model if all five team members fully contribute to the common effort. Without any additional evidence, the team success is only 50% probable, as we can see in the yellow node at the bottom of the network. The blue node, named “Team Members Are Mutually Supportive” is caused by the five nodes corresponding to the team members (because it is up to them to be or not to be mutually supportive) and by the purple node, named “Team Leader Fosters Mutual Support Within Team” (because, if true, it would increase the probability of a mutually supportive teamwork, and, if false, it would decrease that probability). Finally, the 9 observable signs of a supportive team are shown as the oval nodes. Whether or not each of these signs is true is not fully certain, but if the team is mutually supportive, the probability of each of the signs to be true is quite high (in this model, 90%), and if the team is not mutually supportive, each sign is as probable to be true as to be false. Let us now use this model to consider several illustrative scenarios.

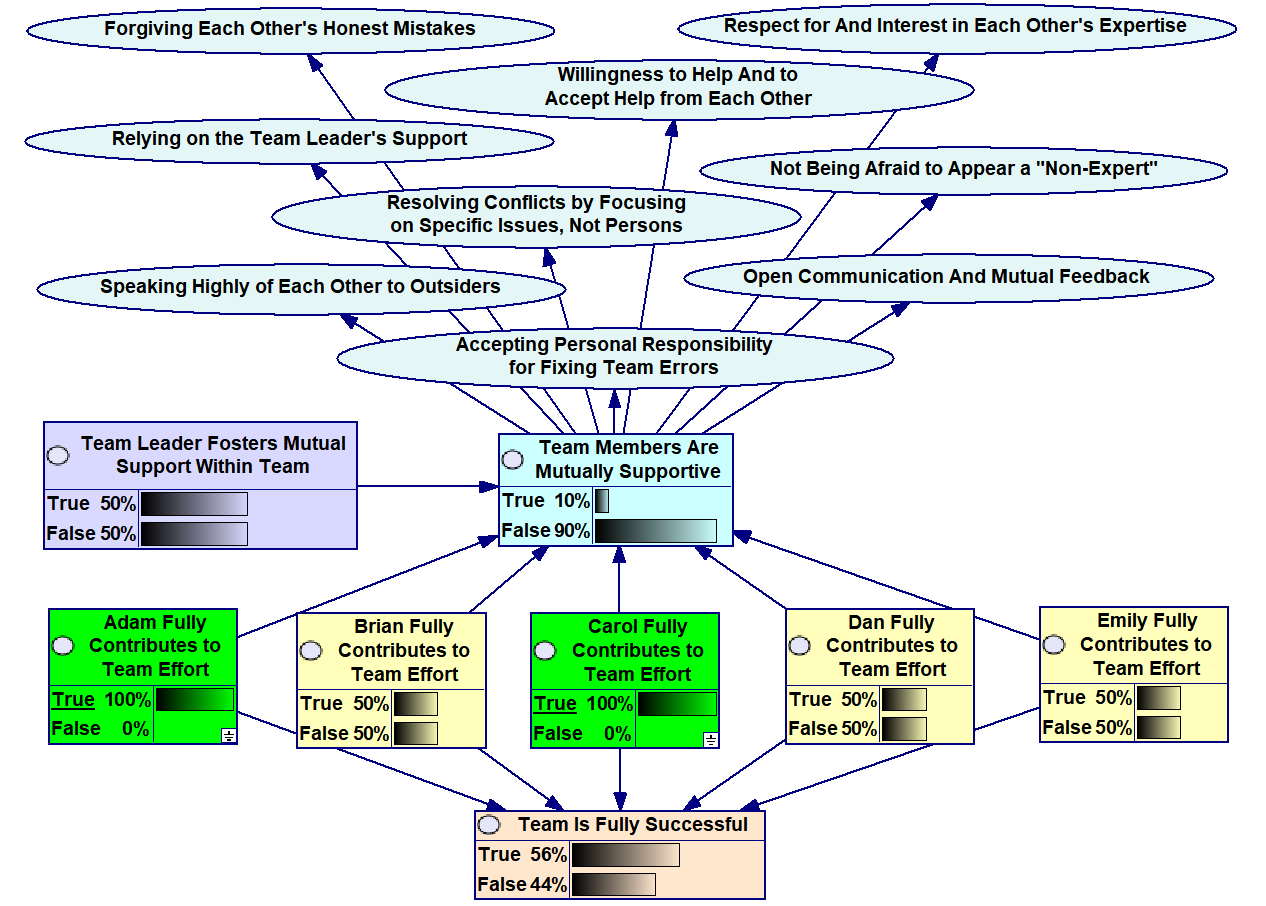

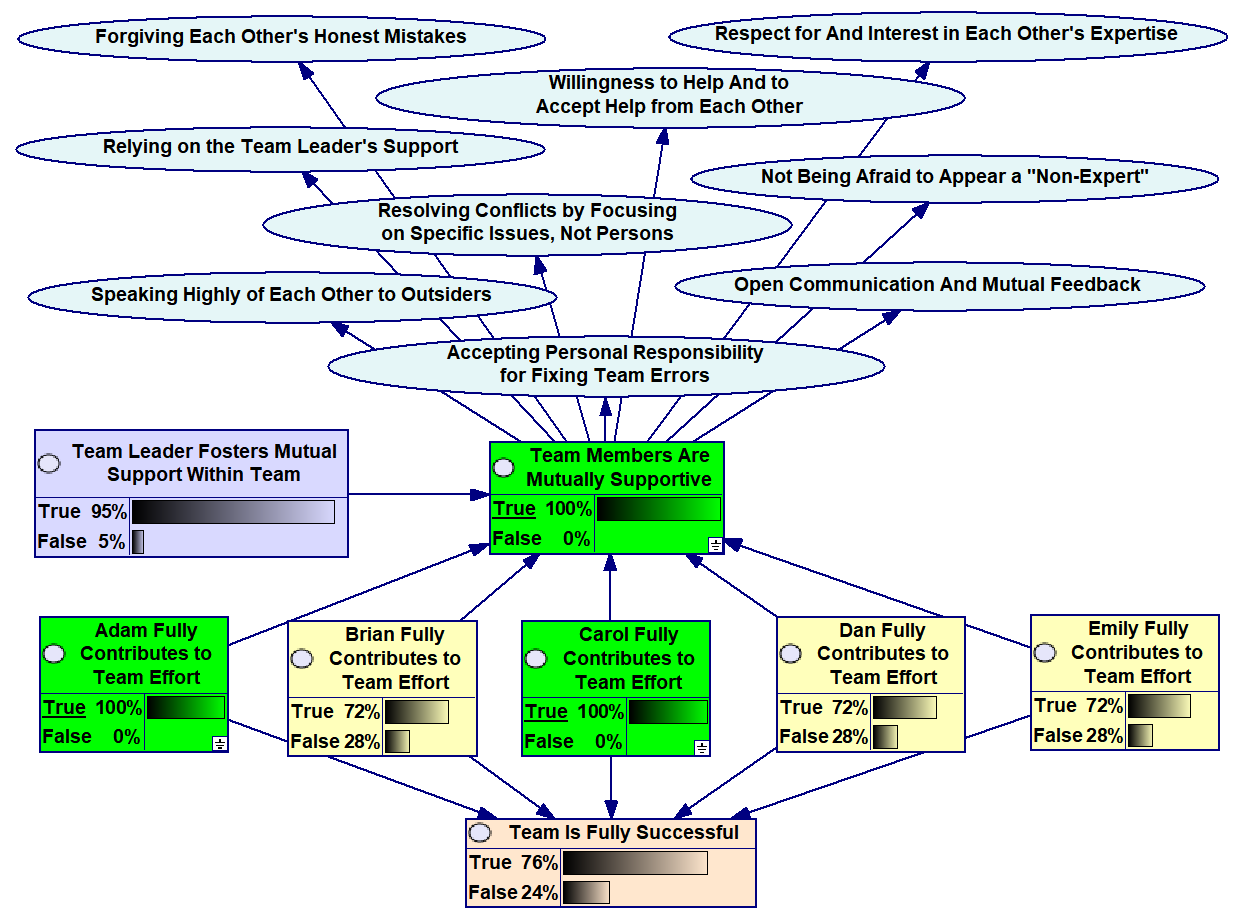

First, let us assume that two team members, Adam and Carol for example, fully contribute to the team effort. Due to this evidence, the probabilities of the other 16 nodes change as shown here:

Figure 2

Comparison with Figure 1 above shows that, although the probability of the full team success increased from 50% to 56% due to Adam’s and Carol’s work, the probability that Brian, Dan and Emily each contribute fully stays at 50%. In other words, despite Adam’s and Carol’s efforts, the team remains a group of independent individuals rather than a coherent unit. We can also see that the probability that the team is mutually supportive did increase from 6% in Figure 1 to 10% in Figure 2, but a 10% probability is not sure evidence of mutual team support. Furthermore, the 10% probability increases significantly, to 19%, if we assume that the team leader fosters mutual support:

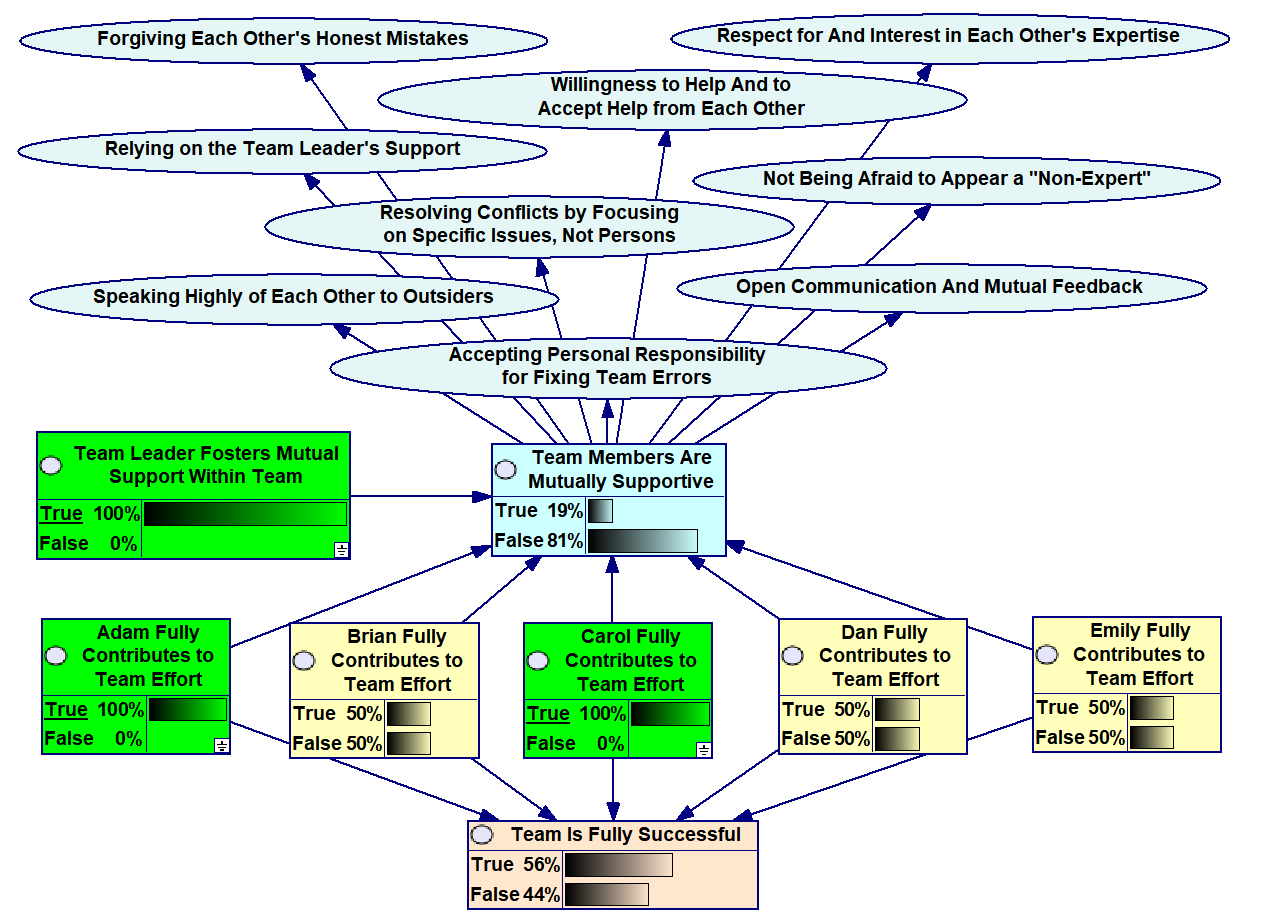

Figure 3

But even with the leader’s positive influence, there is still no sure evidence of mutual support, and hence the full contributions from Brian, Dan and Emily have not increased from the initial 50%. This is how the model accounts for what I stated above: that only the team members can decide to be mutually supportive; the leader alone cannot “magically” achieve that. Next, let us assume that somehow we do have evidence that the team is mutually supportive (we will discuss the “somehow” part below):

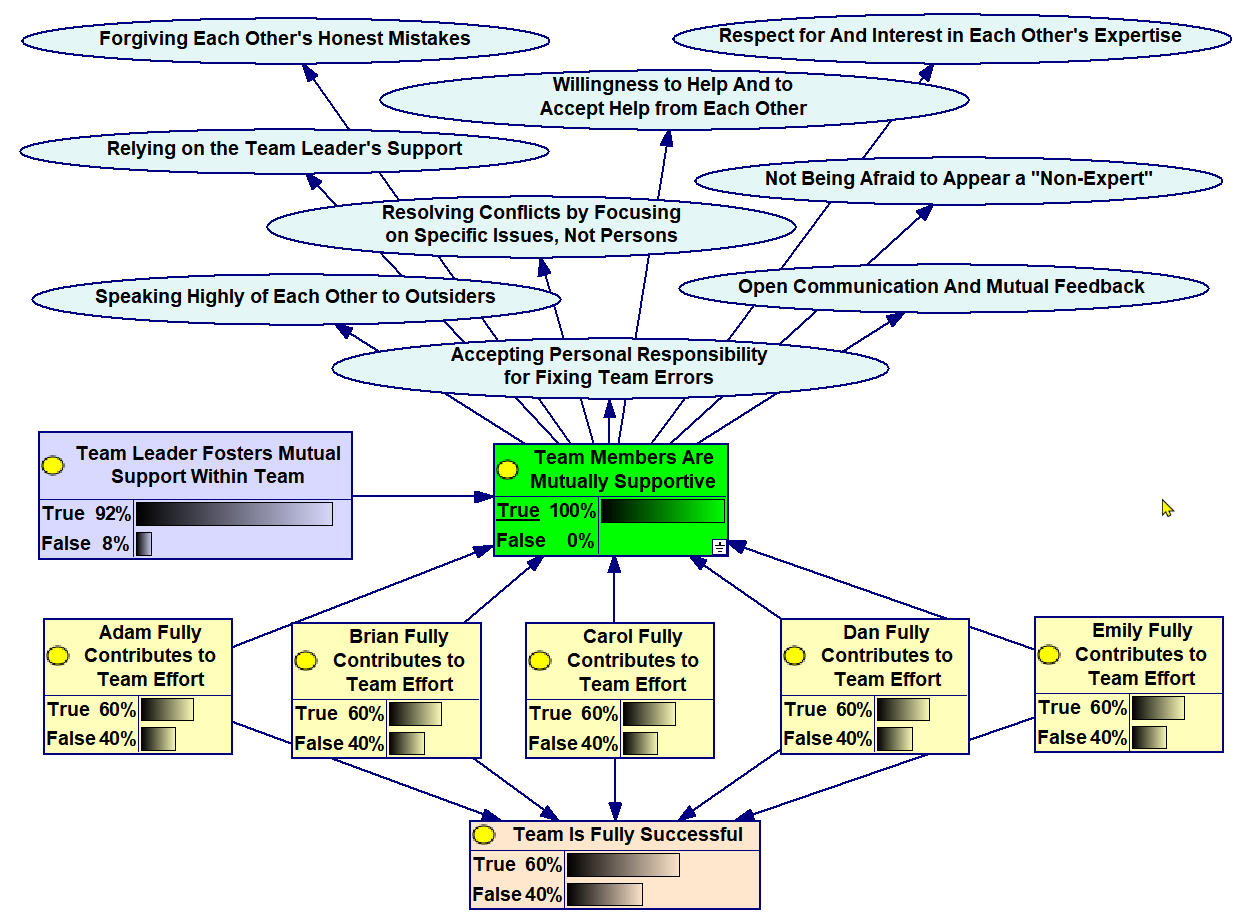

Figure 4

Due to the evidence that the team is mutually supportive, we see that the probability of each of the five team members contributing fully jumped by 10%: from 50% in Figure 1 to 60% in Figure 4.

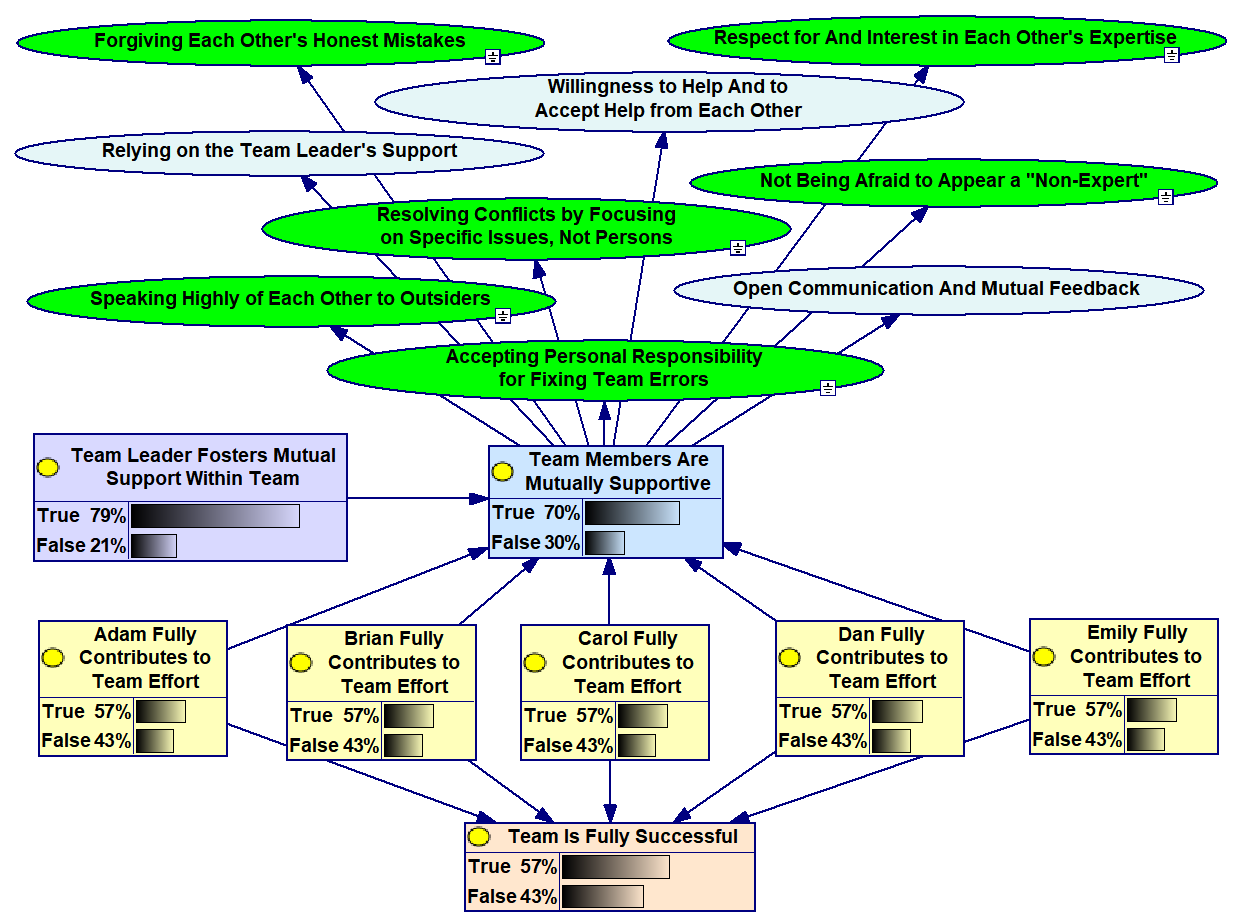

Now we are ready to explore the synergistic effect of the mutual support that is the main focus of this post. Let us say that in a mutually supportive team, we also know that Adam contributes to the team effort fully. Notice that the probabilities of the other 4 team members’ full contributions are no longer 60% as in Figure 4; in fact, they are now increased by 4% to become 64%:

Figure 5

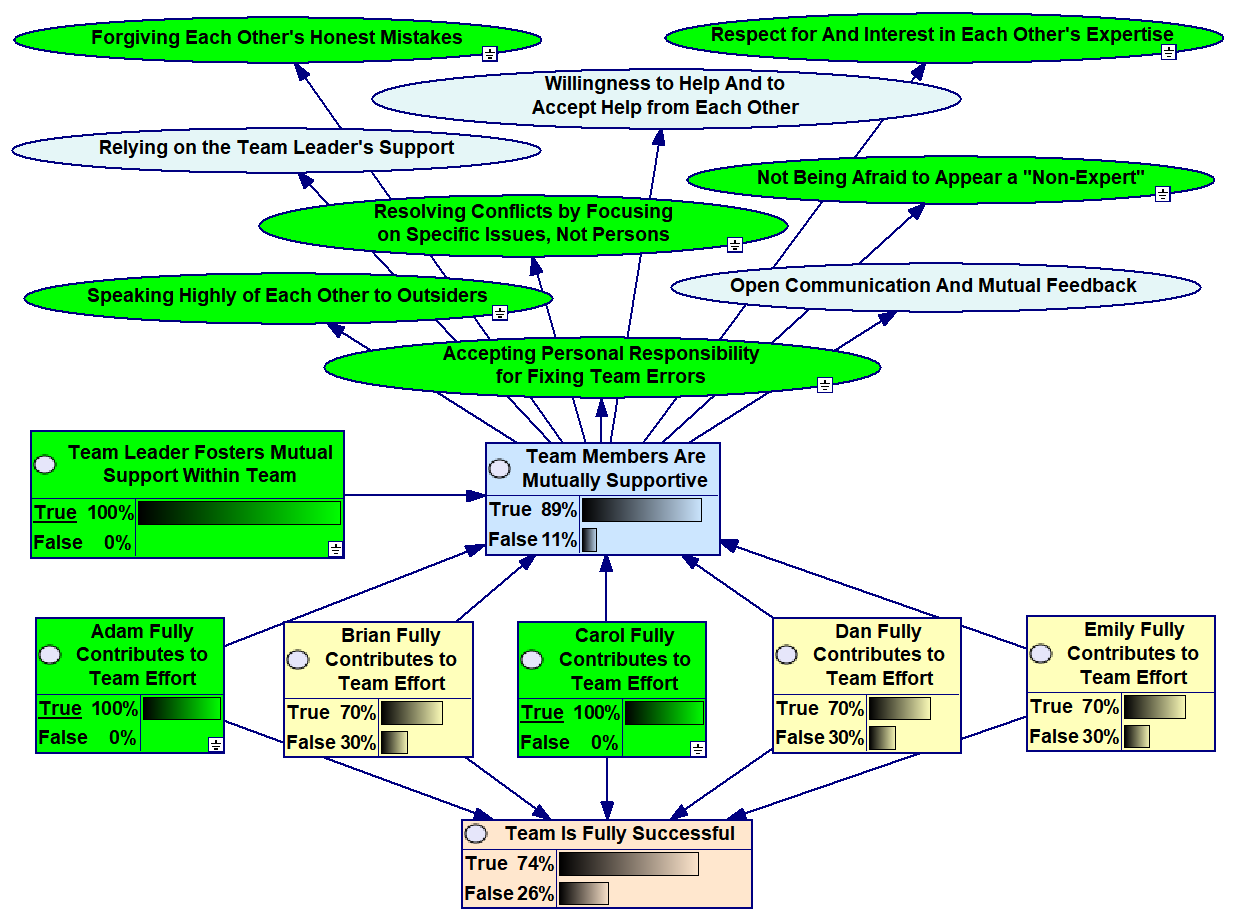

The synergy of mutual support can be expressed as “just one team member’s full contribution motivates the others to contribute more fully.” Let us continue one step further and assume that, in the mutually supportive team, Carol also fully contributes to the group effort:

Figure 6

With two team members fully contributing, each of the other three team members are now 72% probable to contribute fully: a jump of 8% from the 64% in Figure 5. By comparing Figures 4, 5 and 6, we should note a cumulative synergistic effect of mutual support. Namely, one team member’s full contribution motivates the remaining team members to be full contributors by 4%; with the two team members fully contributing, each of the other three is motivated to increase their contributions not by 4% but by 8%. Thus, in a mutually supportive team, when more people “pull their load” fully, it becomes progressively easier for the remaining team members to do that same. One could even speculate that this is a version of Solomin Asch’s “group conformity” effect (Asch, Solomon, "Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion of judgments". Groups, Leadership and Men: Research in Human Relations, Carnegie Press. pp. 177–190, 1951): the team members who have not yet joined in the full team effort are increasingly compelled to conform to the joint effort, and so more and more of them do join, and the pressure increases on the remaining “non-joiners” to join.

Now let us turn to how we could know that the team is mutually supportive. Most often, the evidence of mutual support is indirect, in that it can be inferred from observable behaviors and attitudes of the team members. In our Bayesian network model, we explicitly included 9 such signs of a mutually supportive team. Let us illustrate the effect of observing these signs by assuming that 6 of them are observed to be true. These are the green-colored oval nodes in this network:

Figure 7

We see that due to these 6 observed signs, the probability of mutual team support increased from 6% in Figure 1 to 70% in Figure 7. Because this increase is not all the way up to 100%, the evidence based on several, but not all, signs is partial. The implied effect on the team members is more moderate than that observed in Figure 4 where the evidence for full (or, as I called it, “sure evidence”): the probability of their full contribution increased from 50% not to 60% as in Figure 4, but to 57%. The synergistic effects are similarly more moderate when the evidence about team support is partial. This can be seen by assuming that Adam contributes fully, and then comparing the probabilities of full contributions from Brian, Carol, Dan and Emily as shown in Figure 5 and as shown in this figure:

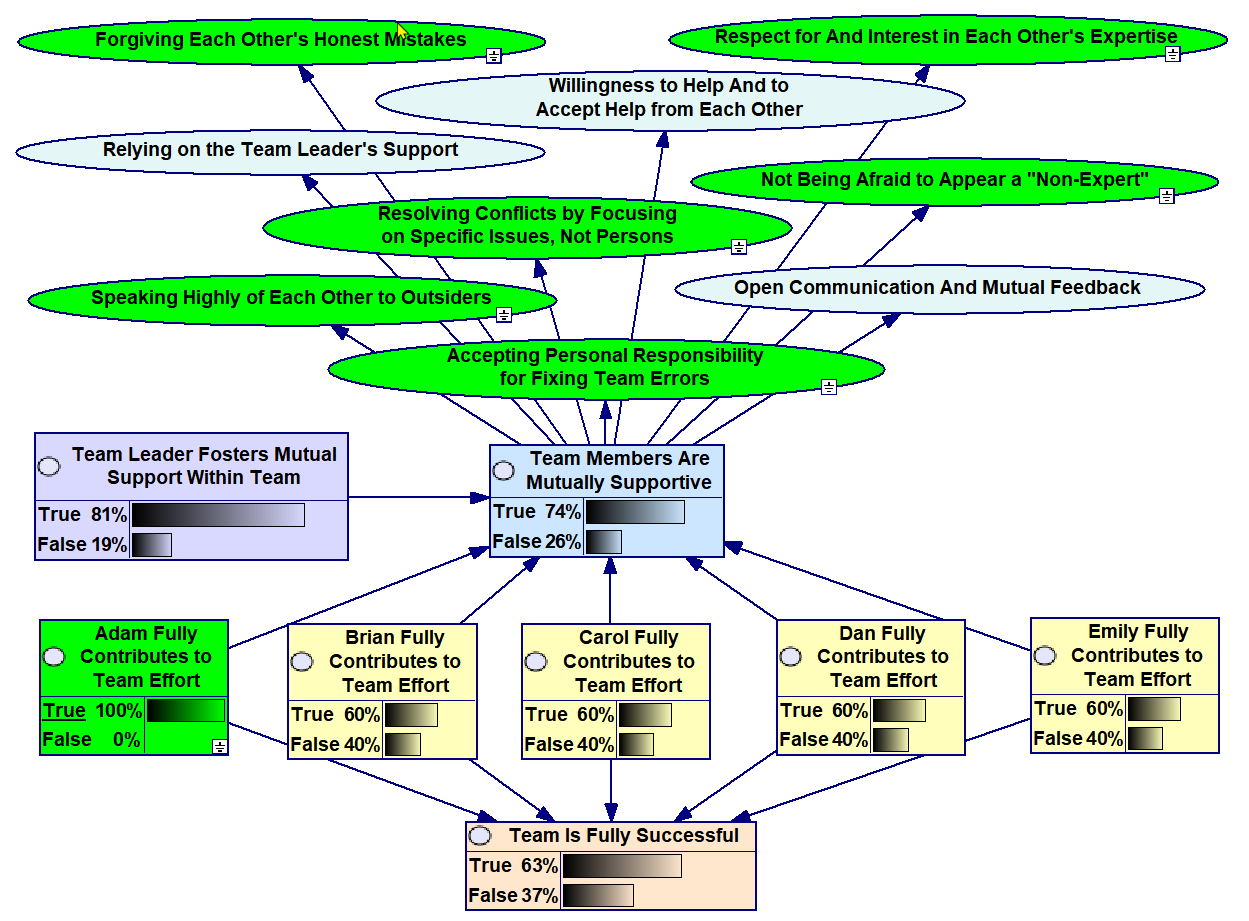

Figure 8

The synergistic effect of the sure evidence about the team being supportive is the increase of the probabilities of these four team members by 4%: from 60% (in Figure 4) to 64% (in Figure 5). By contrast, the partial evidence due to the 6 observed signs has a smaller synergistic effect: the probabilities of the full contributions from the four team members increased by a smaller amount of 3%: from 57% (in Figure 7) to 60% (in Figure 8).

What about the role of the team leader? When we observe 6 signs of a mutually supportive team and thus obtain partial evidence that the team is mutually supportive, what is the effect of a leader who fosters the mutually supportive teamwork and how does it compare with the effect of a leader who does not? Let us first assume that the leader does foster a supportive environment, and continue assuming that only Adam contributes fully. Here is how this affects the probabilities of full contributions from Brian, Carol, Dan and Emily:

Figure 9

We see that the effect of such nurturing team leader: the probabilities of the four team members’ full contributions have become 63%, not 60% as in Figure 8 (where we made no assumptions about the leader’s role). Thus, even though the supportive team environment is created by the team members themselves, a leader can significantly increase the positive synergy of the team’s mutual support by fostering it. A similar positive effect of the leader can be seen in this example, where we assume that both Adam and Carol contribute fully:

Figure 10

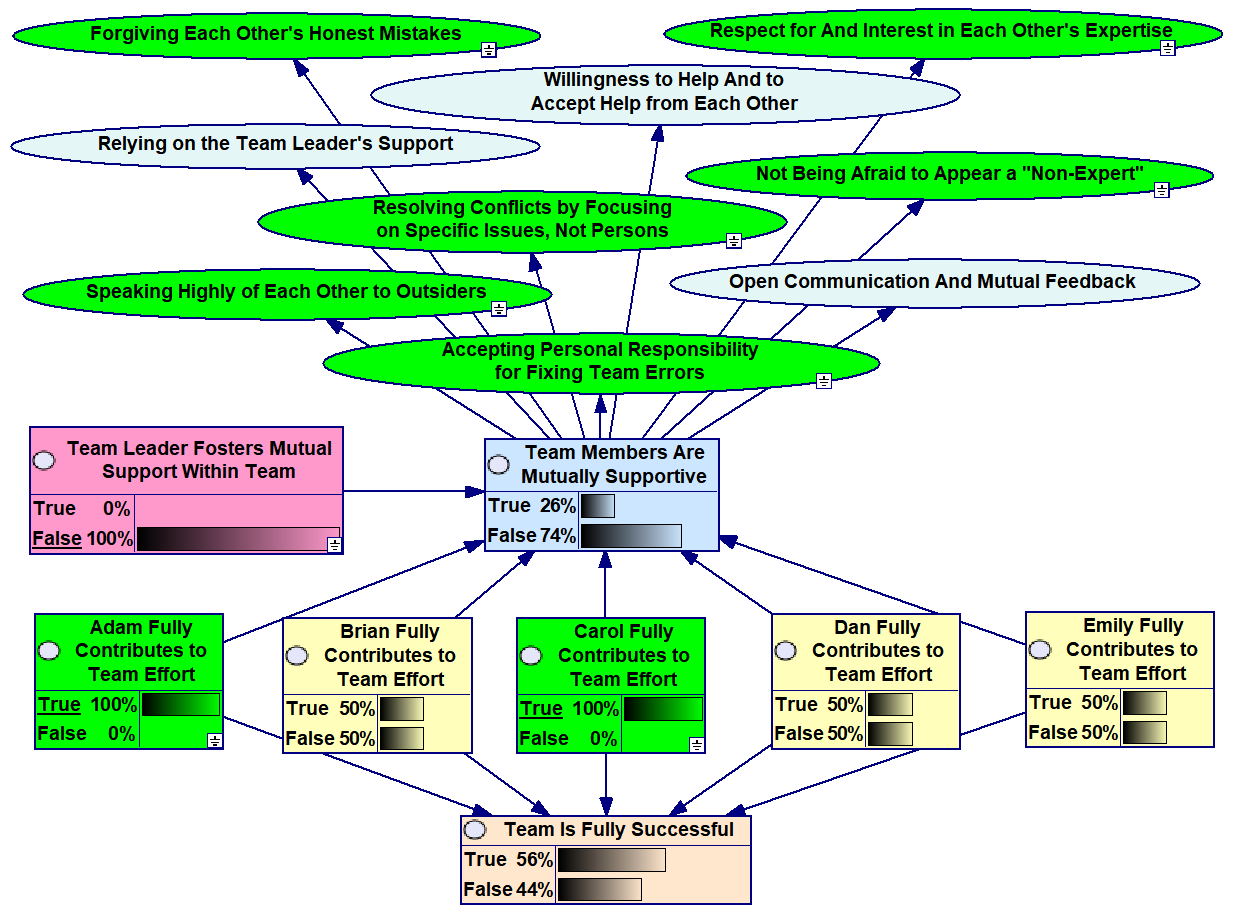

Conversely, a leader who neglect to foster mutual support within their team can have a significant detrimental effect:

Figure 11

Compare this figure with Figure 2 above, where we had no evidence about the team being supportive, nor any assumptions about the leader. We see that an ineffective team leader has completely negated the mutually supportive team’s synergy. Indeed, despite the assumptions made in Figure 11 that the team members exhibit signs of mutual support and the that two team members contribute fully to the joint effort, the probability that each of the other 3 team members would also contribute fully remains at 50%. In the absence of the leader’s fostering effort, the team can only achieve the same level of success as a group of separate individuals. To see that, compare the probability of the node “Team Is Fully Successful” being true as shown in Figure 11 and as shown in Figure 2.

I began this post by quoting W. C. H. Prentice’s treatise on leadership. But I also stated that it is beyond any team leader’s capabilities to create a mutually supportive team environment: that is up to the team members themselves. However, I hope the examples discussed in this post make a convincing case that the benefits of the synergy of work efforts that characterizes mutually supportive teams can be significantly enhanced by a leader who fosters that synergy, and it can be essentially nullified by a leader who fails to do so.